Many have

questioned why it took the tragedy at Sandy Hook to jump start the debate on gun

control, a massacre so horrific that even some staunchly pro-gun politicians have

started to suggest that perhaps some new regulations might be in order.

|

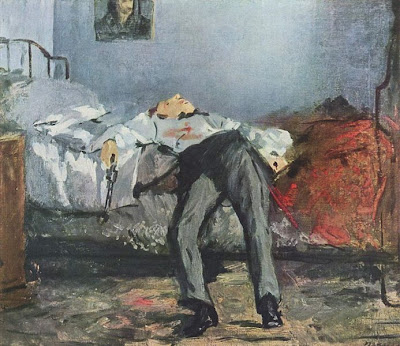

| "The Suicide" Edouard Manet, |

This

outpouring of support for tighter gun control was due largely to the fact that

the Sandy Hook massacre involved the slaughter of “innocents.” Young school

children are seen by many as the most vulnerable, unsullied and worthy members

of our society (unless you include unborn fetuses and the rich, whose worth to

society is unquestioned).

This

distinction between worthy and unworthy victims has permeated the discourse on

gun control on both sides of the issue, with the focus being on how to make our

schools safer (i.e., protecting the “innocents”) rather than how to make

society safer or how to cut the overall social costs associated with gunshot

wounds and deaths.

Yet, as

tragic as it is for children to be gunned down at school, school

shootings make up only a tiny fraction of the total annual gun deaths (less

than 300 since 1980, or less than 10 per year). The sad reality is that

tens of thousands of Americans die each year from gun violence, primarily due

to suicide. In 2010, there were 19,392

gun-related suicides, or 63.6% of the total gun-related deaths, according to Wikipedia. In

contrast, there were 11,078 gun-related homicides, or 36.4% of the total. Very

few of the homicides occurred at schools or other public settings. Nevertheless,

President Obama promised on January

16 to make our schools safer by keeping guns out of the wrong hands and

improving mental health surveillance and services. Like his sanctimonious colleagues

in Congress and the media, the focus is on the “innocents,” while the bulk of

gun victims are ignored.

Biggest Bang for the Buck: Depression

or Psychopathy?

In one

sense, the discussion of better mental health monitoring and treatment is welcome.

For too long mental health services have been inaccessible or unaffordable to

many who need them, while prejudice and shame prevent some from attempting to

obtain these services even when they are accessible.

The problem

is that this aspect of the discourse has focused on almost entirely on psychopathic

rampages, which account for very few gun deaths, while virtually ignoring

depression, PTSD and other conditions that lead to suicide, which accounts for

the overwhelming majority of gun deaths. From the perspective of cost

effectiveness, it would make a great deal of sense to improve mental health

access and services for everyone who needs it—not just those who are seen as

potential homicidal maniacs.

Another

problem with the mental health “solution” is that it tends to be discussed in

essentially moralistic and prejudicial rather than rational terms. For example,

Obama’s call for schools to become “more nurturing” implies that mean teachers or impersonal

schools are somehow responsible for school shootings. His call for more mental

health workers in the schools to curb “student-on-student violence” (rather than to treat all student

mental health conditions) suggests a distinction between the worthy but rare victims

of school rampages, and the less worthy but abundant victims of depression,

anxiety, and stress (conditions which, if left untreated, could lead to suicide).

His call for more police on campuses sends the message that school shooters are

bad guys who must be punished or killed, rather than troubled youth in need of

help. Yet there is no clear evidence that

school safety officers have any effect on reducing crime or violence at school.

Moralism is

also behind the lynch mob demanding a national registry for the mentally ill

and the denial of their second amendment rights. The assumption is that because

some crazy people have committed shooting rampages, that all crazy people are untrustworthy and violent and therefore

need to be carefully monitored and controlled. Yet statistically, crazy people

are no more likely than anyone else to commit acts of violence. Thus,

identifying them and preventing them from buying guns should have only a

nominal effect on the total number of annual gun deaths. On the other hand, the

implementation of a national registry could scare away many people who need

mental health services from seeking help, thus putting themselves (and possibly

the public) at greater risk.

A Rational Person in the Asylum? (Or Not)

One would

think that mental health practitioners would take this unique opportunity to

talk about depression, PTSD, and other problems that can lead to suicidal

thoughts, now that the media has latched onto the idea that the government

might do something to improve access and affordability of mental health

services. Yet when the media interview mental health experts about the role of mental

health in reducing gun violence, the experts rarely mention suicide. They, too,

seem to be caught up in the moralism and hysteria (or perhaps they were told in

advance to avoid mentioning suicide since it is a downer, far less titillating

than massacres and therefore bad for advertising).

Of course

those who commit suicide rarely take out large numbers of “innocents” in the

process. They simply shoot themselves, often when no one is watching.

Furthermore, they have made their own decision when and how to die, in contrast

to the “innocents,” whose choice was made for them by their murderer.

Yet suicide,

like school violence, has significant social costs, including the loss of

income and the emotional trauma for surviving family members (including the “innocents”

they leave behind). Suicide can require emergency services, often at the

taxpayers’ expense. It is disruptive to colleagues who must pick up the slack

at work as they mourn the loss of their workmate and friend; and to their bosses,

who must suddenly find a replacement; and to landlords, who lose rental income

while their bloodied apartment is being cleaned.

What About Gun Control?

Gun

enthusiasts like to point out that during the 10-years assault rifle ban,

there was no reduction in gun fatalities in the U.S. However, the ban was

pretty leaky, with loopholes that allowed the purchase of numerous high powered

weapons. It also did nothing to reduce the 270 million guns circulating in the U.S. (close to nine guns per every 10 people).

However, it

is hard to imagine how a total reduction in circulating guns (rather than

temporary bans on the sale of certain types of guns) could not reduce gun

fatalities. Consider that slightly more than 50% of suicides in the U.S. are

committed with firearms. When guns already exist in the household, they provide a quick and

highly efficient means of killing oneself. Since other methods are less

reliable, more painful, or more difficult to plan and carry out, reducing

access to guns should reduce the number of suicide attempts, as well as the

success rate.

A reduction

in the number of guns in circulation also ought to reduce accidental gun deaths

(which average around 600 per year). Though statistically rare compared

with suicides and homicides, slightly more than half of the accidental gun deaths

involve children, and

thus account for far more deaths of “innocents” than do school rampages. However,

the otherwise upstanding adults whose negligence or irresponsibility contributed

to these accidents are far more sympathetic (and formidable, when it comes to

threatening their right to bear arms) than are crazies like Adam Lanza (the

Sandy Hook killer).

Poverty is Violence

Since the

pundits and politicians have taken suicide off the table, let’s talk about

homicide, because even here there is a lot of moralism and prejudice in the

public discourse. Certainly it is scary to imagine oneself or one’s child the

victim of an armed robbery, rape, terrorist attack or school massacre. But for

most Americans this fear is exaggerated. In the majority

of homicides, the victim is poor, with a prior criminal record.

One might

justly wonder why the left isn’t calling for “economic justice” or programs to

help ex-cons integrate back into society, in addition to gun control and improved

mental health access, since this could help reduce the number of gun deaths.

But then again, ex-cons and the poor, in general, are not considered worthy

victims. If we really wanted to reduce their unnecessary deaths, we would have

to provide housing to the homeless so they didn't die of exposure. Employers would have to slow down the

factories and provide sufficient safety equipment so their low income employees

would stop dying on the job. They'd have to provide healthcare so they could keep their employees' diabetes and hypertension under control, and increase their pay so they had

less stress and material insecurity (which

contribute to their elevated rates of hypertension, diabetes, cancer and heart

disease).

Lastly, a

significant fraction of the homicide victims are women who were killed by their

partners. In 2000, according to the Violence Policy Center,

1,342 women were shot to death by their partners (about 50% of the total

domestic violence deaths). But why worry about a thousand dead women (some of

whom left behind orphaned “innocents”) when there are ten innocent

school children who need protecting?

No comments:

Post a Comment